When Protocol Parsing Leaks Into Application Logic

root@thebughunter:~$ cat header_injection.txt

Target: GitLab Instance

Vulnerability: CRLF Injection → Host Header Poisoning

Impact: Application-Layer Open Redirect

Status: Confirmed and Fixed

The Short Version

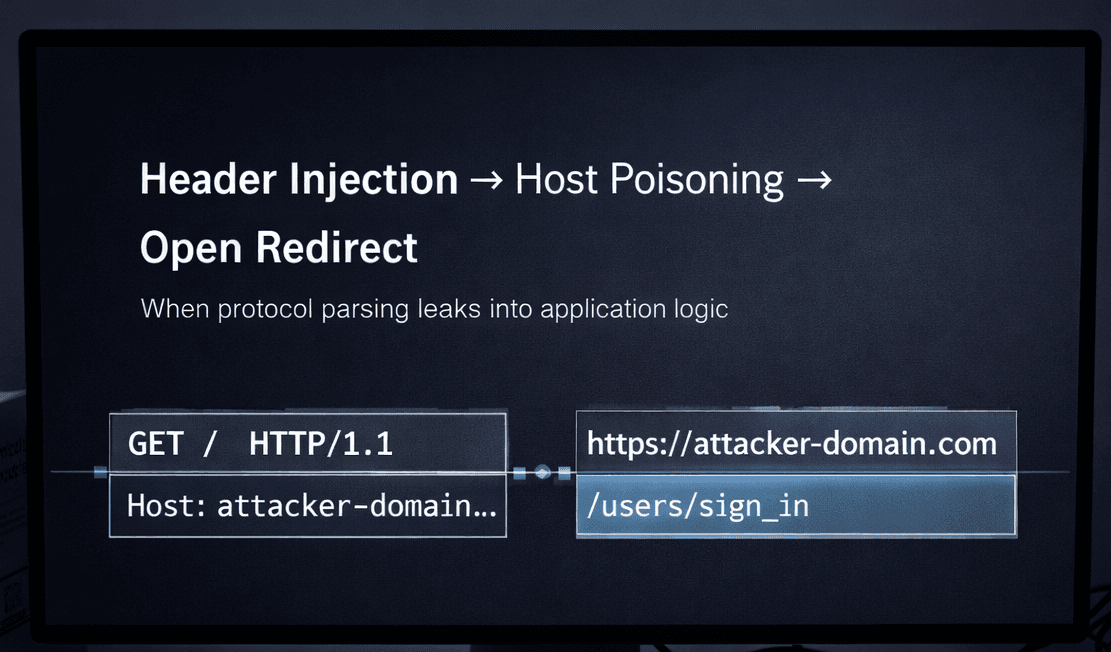

I found a way to inject arbitrary headers into HTTP requests by abusing how the server parsed URL-encoded CRLF sequences. This let me overwrite the Host header and trick the application into redirecting users to an attacker-controlled domain.

Sounds complicated? Let me break it down.

What Even Is CRLF Injection?

CRLF stands for Carriage Return (\r) and Line Feed (\n). In HTTP, these characters separate headers from each other and from the body. When a server doesn't properly sanitize these characters in user input, you can inject your own headers into the response.

The URL-encoded versions are:

%0d= Carriage Return (\r)%0a= Line Feed (\n)

If a server decodes these and treats them as actual line breaks, you've got a problem.

Finding the Injection Point

I was poking around a GitLab instance when I decided to test for CRLF injection in the URL path. My first test was pretty simple - inject an invalid HTTP version and a bogus header to see if the server would choke on it.

https://gitlab.target.com/%20HTTP/9%0D%0ATransfer-Encoding:%20nonexistent%0D%0Ax-end:%20a

Breaking this down:

%20- Space characterHTTP/9- A non-existent HTTP version%0D%0A- CRLF sequenceTransfer-Encoding: nonexistent- Invalid header- Another CRLF and a dummy header to close things out

The server responded with a 505 HTTP Version Not Supported error.

WHY THIS MATTERS

A 505 response to HTTP/9 means the server actually parsed my injected protocol version. It didn't just treat my entire input as a URL path - it interpreted the CRLF sequences and tried to process what came after as HTTP headers.

This confirmed the server was vulnerable to CRLF injection. Now the question was: what can I actually do with this?

Escalating to Host Header Poisoning

Here's where it gets interesting. If I can inject headers, can I inject a new Host header?

https://gitlab.target.com/%20HTTP/1.1%0d%0aHost:%20attacker.com%0d%0a%0d%0a

What I'm doing here:

- Injecting a valid HTTP version (

HTTP/1.1) - Adding a CRLF

- Injecting my own

Host: attacker.comheader - Double CRLF to end the headers section

And it worked. The server's response came back with:

HTTP/1.1 302 Found

Location: https://attacker.com/users/sign_in

The application took my injected Host header and used it to build the redirect URL. It even appended its default login path (/users/sign_in) to my domain.

Why This Is Bad

WHAT AN ATTACKER CAN DO

WHY IT'S SNEAKY

Think about it from a victim's perspective. They get a link that starts with https://gitlab.target.com/... - looks legit, right? They click it, and suddenly they're on attacker.com/users/sign_in looking at what appears to be a GitLab login page.

The Root Cause

This vulnerability exists because of a mismatch between how different layers handle the input:

- The web server decodes URL-encoded characters in the path

- The HTTP parser interprets CRLF sequences as header separators

- The application trusts the Host header for building URLs

Each layer is doing its job correctly in isolation. The problem is that nobody expected URL-encoded CRLF sequences in the path to survive long enough to affect header parsing.

KEY INSIGHT

Protocol parsing (HTTP) and application logic (URL routing, redirects) need to be completely isolated. When they're not, weird stuff like this happens.

How to Test for This

If you want to look for similar vulnerabilities:

Step 1: Test for CRLF interpretation

Try injecting an invalid HTTP version:

https://target.com/%20HTTP/9%0D%0AX-Test:%20injected

If you get a 505 or similar protocol error, the server is interpreting your CRLF sequences.

Step 2: Try injecting various headers

https://target.com/%20HTTP/1.1%0d%0aHost:%20your-server.com%0d%0a%0d%0a

Check if any redirects or links in the response use your injected host.

Step 3: Check for cache poisoning potential

If the response gets cached with your poisoned Host header, you might have a cache poisoning vulnerability too. That's a whole other can of worms.

Mitigation

For developers dealing with this:

- Reject CRLF in URL paths - Don't allow

%0dor%0ain URL paths, period - Validate Host headers - Compare against a whitelist of expected hosts

- Use absolute URLs carefully - Don't blindly trust the Host header for building redirect URLs

- Defense in depth - Apply protections at multiple layers (reverse proxy, web server, application)

What Else Could This Lead To?

I focused on the open redirect because it was the clearest impact I could demonstrate. But CRLF injection opens the door to a lot more if you dig deeper.

Response Splitting / XSS

If the injection point reflects into the response headers, you can potentially inject a double CRLF and start writing your own response body. That means arbitrary HTML, which means XSS.

%0d%0a%0d%0a<script>alert(document.domain)</script>

I tested this but the server wasn't reflecting my input into the response in a way that made this exploitable. Worth trying though.

Session Fixation

If you can inject headers, you might be able to inject Set-Cookie headers:

%0d%0aSet-Cookie:%20session=attacker-controlled-value

Force a victim to use a session ID you control, then hijack their session after they authenticate.

Cache Poisoning

If the response gets cached (by a CDN, reverse proxy, or browser), you could poison the cache with your malicious redirect or injected content. Every subsequent user hitting that cached response would get attacked.

Security Header Bypass

Some applications rely on headers like X-Frame-Options or Content-Security-Policy for protection. If you can inject headers, you might be able to overwrite or neutralize these protections by injecting your own versions earlier in the response.

Request Smuggling

In some configurations, CRLF injection in the request can lead to HTTP request smuggling. You're essentially creating ambiguity about where one request ends and another begins. This gets complicated fast, but the payoff can be huge - bypassing security controls, accessing other users' responses, cache poisoning at scale.

THE TAKEAWAY

CRLF injection is rarely just one vulnerability. It's a primitive that can be chained into XSS, request smuggling, cache poisoning, and more. Always explore what else you can do with it before writing your report.

[REFERENCES]

[RELATED]

Check out my other articles

→ From Self-XSS to Reflected XSS via CSRF

→ IDOR Analysis: Real-World Cases